Introduction

The second activity on decision-making within the GEOCAP programme centered around the private company’s perspective, i.e. the privately financed geothermal operator considering to invest in developing a geothermal resource (although most of the practices will also apply to geothermal state companies). Developing geothermal resources is unlike most other economic activities. This is due mainly to the fact that, at time of spending the major part of the capital expenditure, the productive system (i.e. the subsurface reservoir) is poorly known, resulting in a high technical risk: at time of investing, the forecast project performance will be subject to large uncertainties. There are just too many unknowns in the subsurface reservoir’s properties, and these will only be slowly and parsimoniously revealed as the asset is being developed and produced. Moreover, long pay-out times typically apply to such capital-intensive and risky projects, which exacerbate the technical risks. This calls for a prudent approach, as geothermal operators must balance the perceived risks with the expected financial return resulting from the project: the higher the perceived risk, the higher the threshold for profitability must be in order to obtain, at the corporate level, a balanced portfolio of assets where disappointing projects are counterbalanced by projects that perform better than expected.

There are no generally accepted rules for how to assess risk, nor for how to set the required profit margin as a function of the perceived risks. This applies not only to geothermal companies, but also to the analogous oil and gas exploration and production industry. Companies will have their individual practices to decide whether to pursue a business opportunity. However, in all cases governments can contribute a great deal in terms of either de-risking a project, and/or improving the expected return. To understand this better, a two-day workshop was organized in 2016 (adjacent to the IIGW # 5 conference in Bandung, together with the previous topic on government decision-making), followed by a one-week course in October/November 2017 (at PPSDM, Jakarta).

The course’s contents discussed mainly the issue of how to ‘frame’ an investment problem and, subsequently, how to use integrated technical / business models to quantify, probabilistically, the range of possible outcomes. This enables the project staff to establish a project’s expected outcome, including the uncertainty range around it, which again can be translated into some measure for ‘risk’. Expected outcome and risk can then be offset against each other, which in principle helps the decision-makers to decide whether to further mature a project. Importantly, the quantitative models also enable the users to understand sensitivities: which top drivers determine ‘risk’, and which top drivers are responsible for the ‘expected outcome’? Can these uncertainties be reduced, thereby reducing ‘risk’? Which options exist to steer the project into a more profitable direction as new information is being revealed in time? Should we actively acquire new information for a better design of the facilities to be constructed? If so, what is the value of that information? Which flexibility options in the facilities can be designed upfront to allow striking the option when new information is being revealed? At what cost? How does this improve the project’s expected reward?

This type of questions, including the general business processes of project maturation and decision analysis to deal with complex investment decisions subject to large uncertainties, were studied as part of this activity.

RELEVANCE FOR AND APPLICABILITY TO INDONESIA

After having delivered the two-day workshop in 2016, feedback was given by the class of some 20 participants. Their comments confirmed the perceived relevance and applicability of this topic to Indonesia. Some excerpts are given below:

- “Even after having worked for over 8 years with an Indonesian geothermal Operator, I’ve never heard anything of what you’ve been teaching us on company decision-making. Yet, this knowledge seems crucial for expediting the development of Indonesia’s geothermal resources.”

- “The sooner you can give the full course, the better. Then we can apply your teachings earlier.”

- “I hope someday this course will show the solution for Indonesian conditions. Then it can help us grow and build more geothermal energy in Indonesia.”

- “We learned a new sophisticated way of how to formulate geothermal risk. It is a big opportunity for Indonesia to gain more knowledge and to tackle the problems in the geothermal industry.”

- “The Government should be involved in this kind of workshops / courses.”

- “We received such a lot of new information, especially on how to make decisions.”

- “We liked the multidisciplinary approach in decision-making and how the various types of information from people with different backgrounds come together into one ‘language’.”

- “Very experienced and approachable presenter. Especially the exploration decision exercise was challenging and insightful”.

- “I liked learning about the ‘learning process’ during the life-cycle of a geothermal development, and how anticipating on possible future new information conditions current decision-making.”

Indeed, developing a common ‘language’ between the government institutions and the geothermal operators seems to fulfil a dire need. But also improving a company’s internal business processes will benefit from the methods and practices presented. The problem however is to further disseminate and maintain this practice in Indonesia. A major hurdle is that psychological barriers prevent people from embracing uncertainty, as they rather tend to reduce it, or even ignore it. This is a cultural and psychological attitude that takes a long time and a major repetitive effort to overcome, as experienced in the oil and gas exploration and production sector.

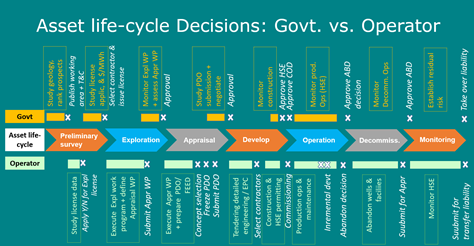

To expedite the development of a geothermal resource, government and operators need to understand in-depth each other’s decision-making processes

GEOCAP ACTIVITY IN THIS TOPIC

During the week’s course (October/November 2017 at PPSDM, Jakarta) with some 20 participants (from institutes and geothermal operators such as ITB/UGM/Syiah Kualah universities, MEMR/ESDM, Halliburton, Pertamina, Supreme Energy), the following subjects were covered jointly by lecturers from TNO and ITB:

- Geothermal energy in Indonesia

- Geothermal asset maturation cycle and associated decisions

- Decision Gate process, Decision Analysis process

- Discounted Cash Flows, cost of capital and discount rate, tax regimes

- Decision criteria, Key Performance Indicators, capital efficiency

- Framing the problem

- Uncertainty modelling, basic probability theory, decision tree analysis

- Valuation, Value of Information, Value of Flexibility, option valuation

- Multi-criteria decision analysis

- Psychology related to uncertainty

- What do managers need to make decisions? What is a ‘good’ decision?

- Portfolio analysis, multi-asset modelling

- Balancing long-term vs. short-term objectives

- What is a good investment climate?

To allow hands-on practical exercises using quantitative models, a dedicated Geothermal Asset valuation tool had been developed, based on XL and therefore compatible with commercial statistical XL plug-in software, which had been installed on all classroom computers (the tool is discussed in the next chapter). This enabled all participants to experiment with Monte Carlo processing of their uncertain modelling input assumptions, resulting in statistical distributions for the project’s Key Performance Indicators (KPI), together with the associated probabilistic time-series (e.g. p90-p50-p10 etc. forecasts). In a subsequent sensitivity analysis, the KPI histograms could then be analysed for which uncertain input variables contributed most to the computed uncertainty of a (output) KPI, thereby triggering a discussion on what remedial action would be possible to improve the project’s expected performance, or reduce the project’s risk.

on XL and therefore compatible with commercial statistical XL plug-in software, which had been installed on all classroom computers (the tool is discussed in the next chapter). This enabled all participants to experiment with Monte Carlo processing of their uncertain modelling input assumptions, resulting in statistical distributions for the project’s Key Performance Indicators (KPI), together with the associated probabilistic time-series (e.g. p90-p50-p10 etc. forecasts). In a subsequent sensitivity analysis, the KPI histograms could then be analysed for which uncertain input variables contributed most to the computed uncertainty of a (output) KPI, thereby triggering a discussion on what remedial action would be possible to improve the project’s expected performance, or reduce the project’s risk.

Materials

CONTACT

- Ali Ashat (ITB)

- Christian Bos (TNO)